History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

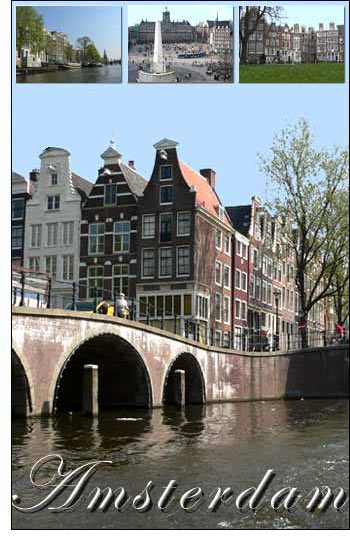

Amsterdam Holland<

Amsterdam museums

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

Amsterdam Holland

|  |

| |

| |

In the main Amsterdam is a city of trade, of hurrying business men, of ceaseless clanging tramcars and crowded streets; but on the Keizersgracht and the Heerengracht you will find the old essential Dutch gravity and peace. No tide moves the sullen waters of these canals, which are lined with trees that in spring form before the narrow, dark, discreet houses the most delicate green tracery imaginable; and in summer screen them altogether. These houses are for the most part black and brown, with white window frames, and they rise to a great height, culminating in that curious stepped gable (with a crane and pulley in it) which is, to many eyes, the symbol of the city.

For the greatest contrast to these black canals, you must seek the Kalverstraat. The Kalverstraat, running south from the Dam, is by day filled with shoppers and by night with gossipers. Damrak is of course always a scene of life, but Damrak is a thoroughfare — its population moving continually either to or from the Amsterdam train station (Centraal Station). But those who use the Kalverstraat may be said almost to live in it. To be there is an end in itself.

For the principal cafés, as distinguished from restaurants, you must seek the Rembrandt’s Plein, in the midst of which stands the master’s statue.

Amsterdam may be a city builded on the sand; but none the less will it endure. Indeed the sand saves it; for it is in the sand that the wooden piles on which every house rests find their footing, squelching through the black mud to this comparative solidity. Some of the piles are as long as fifty ft., and watching them being driven in. I have seen somewhere the number of piles which supported the the Central Station; but I cannot now find them. The Royal Palace on the Dam square stands on 13,650.

The advice to any one visiting Amsterdam is first to study a map of the city and thus to begin with a general idea of the lie of the land and the water. With this knowledge, and the assistance of the trams, it should not appear a very bewildering place. The Dam is its heart: a fact the acquisition of which will help very sensibly. All roads in Amsterdam lead to the Dam, and all lead from it. The Dam gives the city its name — "Amstel dam", the dam which stops the river Amstel on its course to the IJsselmeer. Almost every tram sooner or later reaches the Dam: that is another simplifying piece of information. The course of each tram may not be very easily acquired, but with a common destination like this you cannot be carried very far wrong. One soon learns that the trams stop only at fixed points, and waits accordingly.

On the Dam also is the Royal Palace, which once was the stadhuis, but around 1800 (when Amsterdam was the 3rd city of the French Empire) was offered to Napoleon for a residence. It is interesting to have Amsterdam at one’s feet. Only thus can its peculiar position and shape be understood: its old part an almost perfect semicircle, with canal-arcs within arcs, and its northern shore washed by the IJ.

Also on the Dam is the New Church, which is to be seen more for the tomb of De Ruyter than for any architectural graces. The old sea dog, whose dark and determined features confront one in Bol’s canvases again and again in Holland, reposes in full dress on a cannon amid symbols of his victories.

To return to Amsterdam’s sights, the church which I remember with most pleasure is the Church, which many visitors never succeed in finding at all, but to which I was taken by a Dutch lady. You seek the Spui, and enter a very small doorway on the north side. It seems to lead to a private house, but instead you find yourself in a very beautiful little enclosure of old and quaint buildings, exquisitely kept, each with a screen of pollarded chestnuts before it; in the midst of which is a toy white church with a little spire that might have wandered out of a fairy tale. The enclosure is called The Begijnenhof, or Court of the Begijnen, a little sisterhood named after St. Begga, daughter of Pipinus, Duke of Brabant, — a saint who lived at the end of the 7th century.

The church was originally the church of these nuns, but when the old religion was overthrown in Amsterdam, in 1578, it was taken from them, although they were allowed to retain possession of the court around it.

In 1607 the church passed into the possession of a settlement of Scotch weavers who had been invited to Amsterdam by the merchants, and who had made it a condition of acceptance that they should have a conventicle of their own. One may leave the Begijnenhof by the other passage into Kalverstraat, and walking up the busy shopping street towards the Dam.