History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

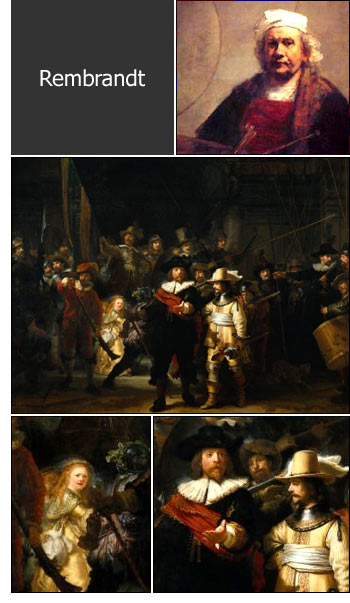

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Rembrandt the artist<

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

Rembrandt the artist

In the year 1669 an old Dutchman called Rembrandt dies in obscurity in Amsterdam. So unmemorable was the death deemed that no contemporary document makes mention of it. The passing of Rembrandt was simply noted, baldly and briefly, in the death−register of the Wester Kerk: "Tuesday, October 8, 1669; Rembrandt van Ryn, painter on the Roozegragt, opposite the Doolhof. Leaves two children."

In the year 1669 an old Dutchman called Rembrandt dies in obscurity in Amsterdam. So unmemorable was the death deemed that no contemporary document makes mention of it. The passing of Rembrandt was simply noted, baldly and briefly, in the death−register of the Wester Kerk: "Tuesday, October 8, 1669; Rembrandt van Ryn, painter on the Roozegragt, opposite the Doolhof. Leaves two children."Yet once, while he was alive, before he painted the famous Night Watch painting, he had been the most famous painter in Holland. Later, oblivion encompassed the old lion, and little he cared so long as he could work at his art. Forty years after his death, Gerard de Lairesse, a popular painter, now forgotten, wrote of Rembrandt − "In his efforts to attain a yellow manner, Rembrandt merely achieved an effect of rottenness.... The vulgar and prosaic aspects of a subject were the only ones he was capable of noting." Poor Gerard de Lairesse!

Today not a turn or a twist of his life, not a facet of his temperament, not an individual of his family, friends, or acquaintances, not the slightest scrap of paper bearing the mark of his hand, but has been peered into, scrutinised, tracked to its source, and written about voluminously. The bibliography of Rembrandt would fill a library. Several lengthy and learned catalogues of his works have been published in volumes so large that a child could not lift one of them. His pictures and paintings, his multitudinous drawings, his etchings, their authenticity, their history, their dates, the identification of his models, have been the subjects of innumerable books and essays. It would take months just to read what has been written about one of Rembrandt's famous paintings: The Night Watch.

People make the long journey to St. Petersburg to see the drawings and paintings by Rembrandt that the Hermitage contains. He is hailed today as the greatest etcher the world has ever known, and there are some who place him at the head of that noble triumvirate who stand on the summit of the painters' Parnassus, Velasquez, Titian, and Rembrandt. Having browsed and battened on Rembrandt, and noted the countless cosmopolitan workers that for 50 years have been excavating the country marked on the art map Rembrandt, you can perhaps understand why our golfer likened the work of his commentators to the incessant activity that his upturning of that grey, lichen−covered boulder revealed.

All this and much more one would have had to unlearn, discovering in the end the simple truth that Rembrandt lived for his art; that he loved and was kind to his wife and to the servant girl who, when Saskia died, filled her place; that he was neither saint nor sinner; that he was extravagant because beautiful things cost money; that being an artist he did not manage his affairs with the wisdom of a man of the world; that he was hot−headed, and played a hot−headed man's part in the family quarrels; and that he was plucky and improvident, and probably untidy to the end, and that he did his best work when the buffets of fate were heaviest.

"... Rembrandt always chooses to represent the exact force with which the light on the most illumined part of an object is opposed to its obscurer portions. In order to obtain this, in most cases, not very important truth, he sacrifices the light and colour of five−sixths of his picture; and the expression of every character of objects which depends on tenderness of shape or tint. But he obtains his single truth, and what picturesque and forcible expression is dependent upon it, with magnificent skill and subtlety.

"... His love of darkness led also to a loss of the spiritual element, and was itself the reflection of a sombre mind....

"... I cannot feel it an entirely glorious speciality to be distinguished, as Rembrandt was, from other great painters, chiefly by the liveliness of his darkness and the dulness of his light. Glorious or inglorious, the speciality itself is easily and accurately definable. It is the aim of the best painters to paint the noblest things they can see by sunlight. It was the aim of Rembrandt to paint the foulest things he could see − by rushlight...."

Had Ruskin, one wonders, ever seen The Syndics at Amsterdam, or the Portrait of his Mother, and the Singing Boy at Vienna, or The Old Woman at St. Petersburg, or the Christ at Emmaus at the Louvre, or any of the etchings?

To a child, the portrait of a painter by himself has a human interest apart altogether from its claim to be a work of art. Rembrandt's portrait of himself at the National Gallery, painted when he was thirty−two, is not one of his remarkable achievements. It is a little timid in the handling, but that it is an excellent likeness none can doubt. This bold−eyed, quietly observant, jolly−looking man was not quite the presentment of Rembrandt that the child had imagined; but Rembrandt at this period was something of a sumptuous dandy, proud of his brave looks and his fur−trimmed mantle. Life was his province.

No subject was vulgar to him so long as it presented problems of light and construction and drawing. Rembrandt, like Montaigne, was never didactic. He looked at life through his eyes and through his imagination, and related his adventures. One day it was a flayed ox hanging outside a butcher's shop, which he saw through his eyes; another day it was Christ healing the sick, which he saw through his imagination. You can imagine the healthy, full−blooded Rembrandt of this portrait painting the Carcase of a Bullock at the Louvre, or that prank called The Rape of Ganymede, or that delightful, laughing picture of his wife sitting upon his knee at Dresden, which Ruskin disliked.

The other portrait of Rembrandt by himself at the National Gallery shows that he was not a vain man, and that he was just as honest with himself as with his other sitters. It was painted when he was old and ailing and time−marked, five years before his death. His hands are clasped, and he seems to be saying − "Look at me! That is what I am like now, an old, much bothered man, bankrupt, without a home, but happy enough so long as I have some sort of a roof above me under which I can paint. I am he of whom it was said that he was famous when he was beardless. Observe me now! What care I so that I can still see the world and the men and women about me − 'When I want rest for my mind, it is not honours I crave, but liberty.'"